To understand the basics which I'm assuming is the reason that you're here, we need to go back to the very beginning and that means starting with understanding what SQL really is. SQL stands for 'Structured Query Language'. Does that clear everything up so we can get to the good stuff? I expect not. The key thing that you need to know though is that you can use SQL to access databases. You can also use SQL to change these databases, updating or removing the data stored there. A final factor to note is that there are several different types (called flavours) of SQL that alter how you write your query ever so slightly. This mainly affects tools/syntax and the core principles that we'll be discussing today are largely consistent, so that isn't something to be too concerned about for the time being. Now that we know a little more about what SQL is, let's begin to understand the basics of queries.

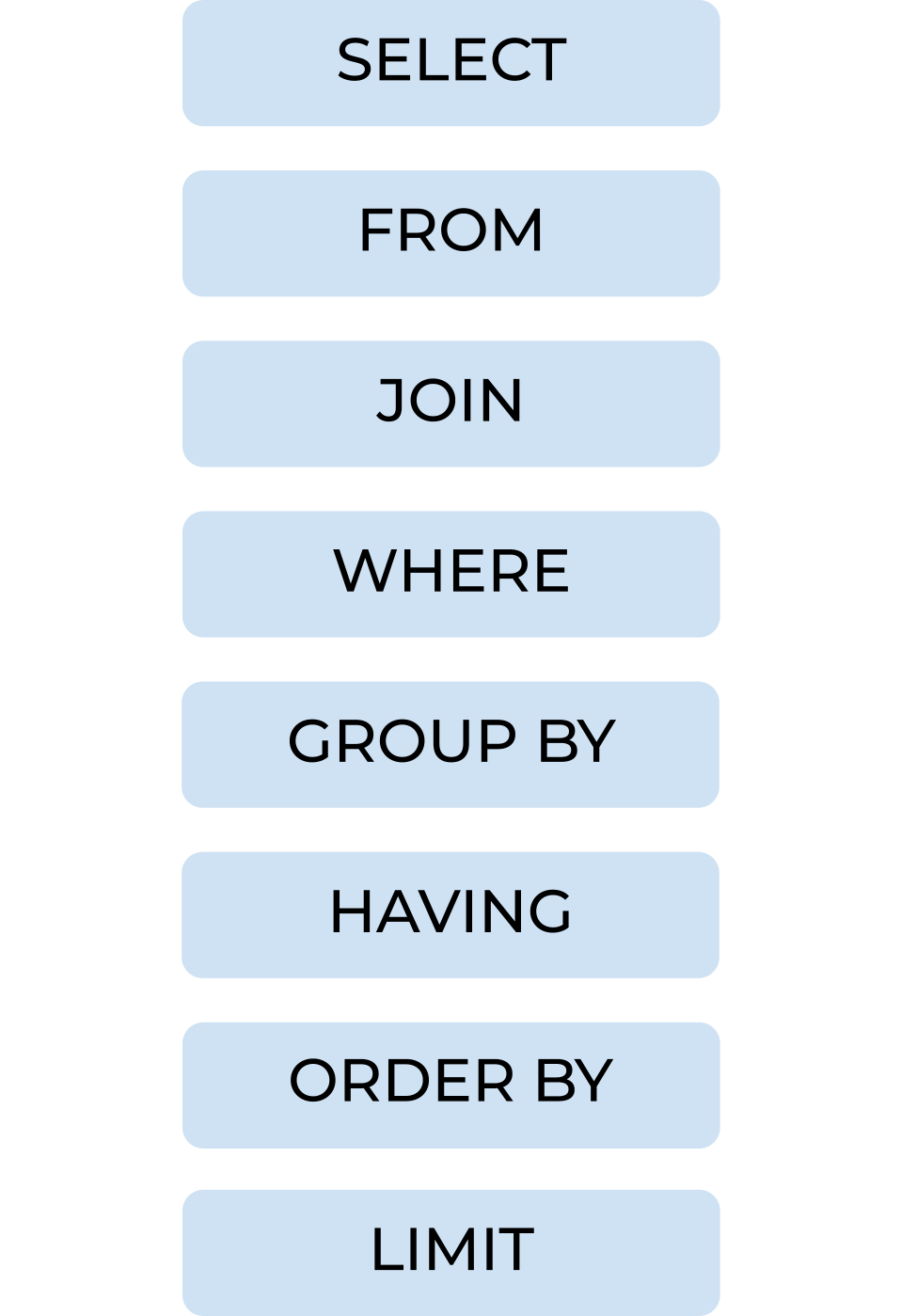

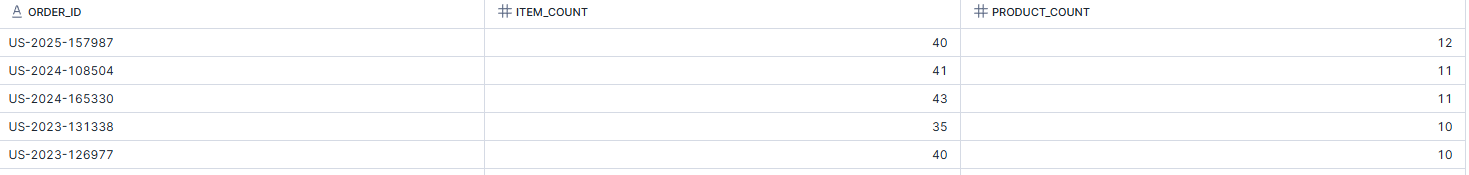

SQL Query Written Order

When you write a request to your SQL database, it has to follow a specific order. Otherwise you'll receive an error with nothing returned. You can see below the specific order that your main query should follow (there are exceptions to this case when you start adding sub-queries etc but for now, understand there is a basic order you need to stick to!).

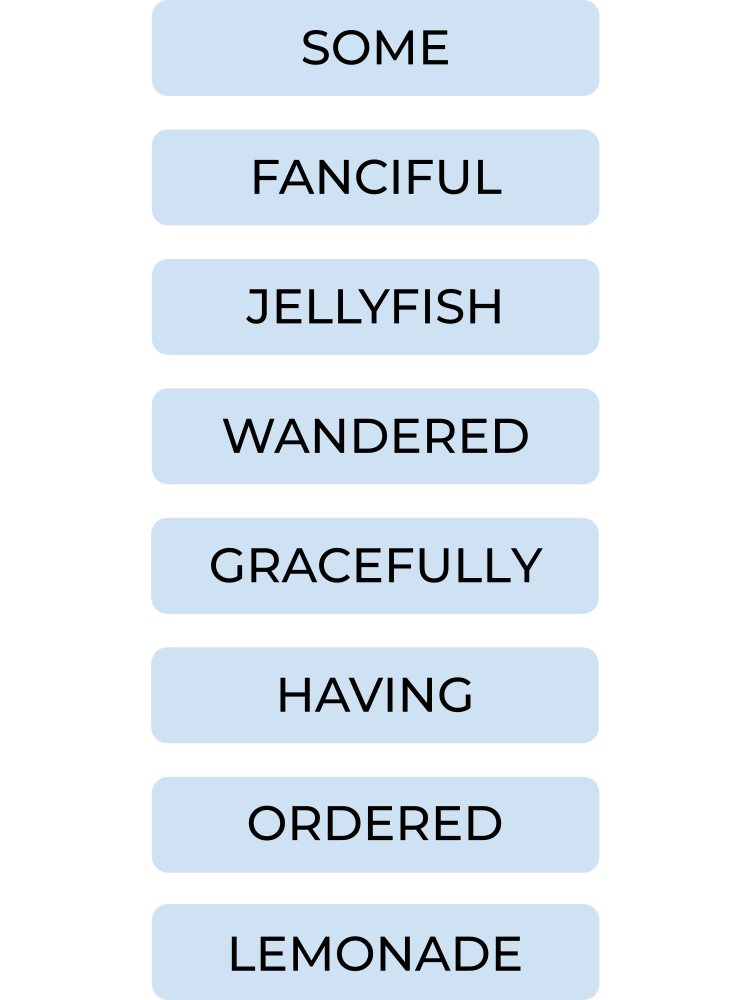

You might find it useful whilst you're learning to come up with a mnemonic. Here's a random one from me but choose your own if you're feeling more creatively inspired. You'll likely remember it better that way too.

Understanding SQL basic clauses

Each clause has a unique purpose to structure your query but importantly, they're not required to be used in every query.

SELECT

The select clause states what columns should be returned by your query. You can use * (an asterisk) to return all columns in your table or separate specified columns with a comma. When things get a little more complicated, you can also add calculations for columns in your SELECT clause. Not only does this include aggregations like sum or average, but also if statements and other fun stuff.

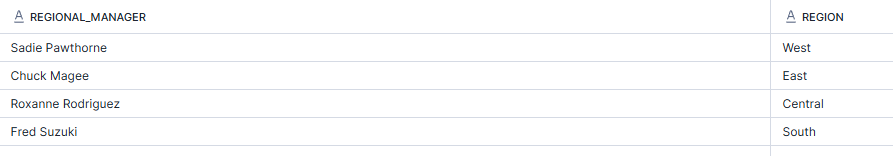

In the example below, I'm asking for all columns from the people table to be returned.

SELECT *

FROM people;

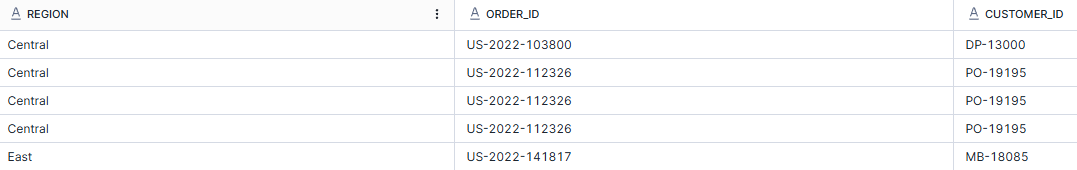

In the example below, I'm asking for the region, order_id and customer_id from the orders table to be returned. It's typically best practice to put the comma in front of your columns to separate them because if you change your mind about the end column, you're far less likely to be left with a lingering comma given that you'd delete it together with customer_id. Note that the columns will be returned in the order that they are stated in the query too.

SELECT

region

,order_id

,customer_id

FROM orders;

FROM

From specifies what table you're choosing from a database. You have the example from above so there's not much point reiterating the same examples.

JOIN

Join is used when you want to collate information from two or more tables. There are numerous types of join that can be specified (a quick google will provide some excellent Venn diagrams with the necessary syntax) and they require join clauses to specify the field they are joining on. Of note, the default join is an inner join so you don't need to specify that join type.

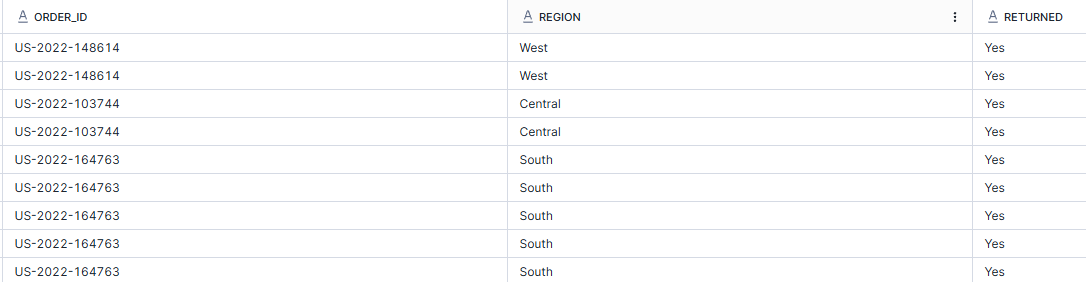

In the example below, I want to return order ID, region and whether the order was returned. To do this, I have to join my orders table with my returns table and this is done on the matching field of order ID. Because there is an order ID in both tables, if I simply wrote order_id = order_id, it wouldn't know which order ID I'm referring to in each case (this usually returns an ambiguous error). Therefore you have to label your tables in the join to refer to them elsewhere in the query. You could also use a join clause of orders.order_id = returns.orders_id but this can be a bit lengthy so I would recommend creating a short form reference.

SELECT

o.order_id

,o.region

,r.returned

FROM orders o

JOIN returns r

ON o.order_id = r.order_id;

In the example below, I'm using a left join to join the orders table with the returns table so I can see all of the orders and then identify which ones have been returned (as the returns table only shows returned orders). I've then joined this table onto the people table to see which regional managers are responsible for the different orders.

SELECT

o.order_id

,r.returned

,p.regional_manager

FROM orders o

LEFT JOIN returns r

ON o.order_id = r.order_id

JOIN people p

ON o.region = p.region;

WHERE

Where acts as a form of filter using the conditional format to eliminate false rows from the returned data.

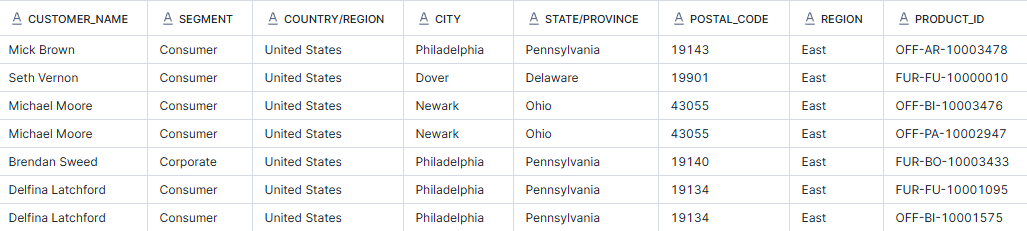

In the example below, I want all columns from the orders table to be returned but only rows for orders sent to the East region. Note that single quotes are typically used for values within a field whilst double quotes are used to refer to columns or tables themselves.

SELECT *

FROM orders

WHERE region = 'East';

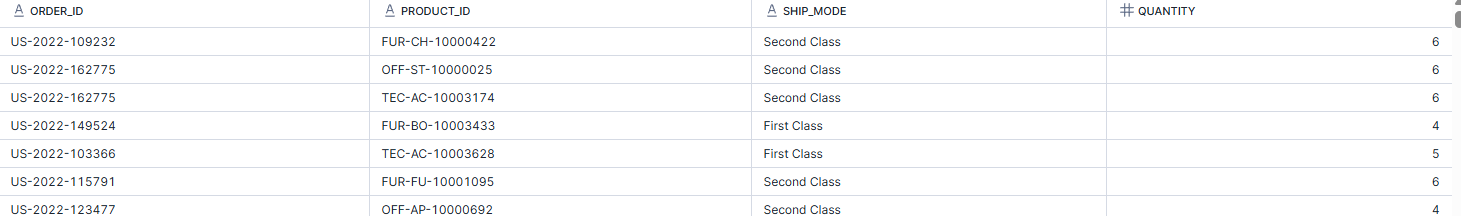

In the example below, I've requested to have the order ID, product ID, ship mode and quantity returned for first class and second class orders which have a quantity of more than 3 of a particular product. To start, this requires some knowledge about the superstore dataset and being aware that each row represents a product within an order rather than the order itself. This is why you can see in the second/third line of my returned screenshot that they have the same order ID but different products. Make sure that what you're requesting is what you want to be returned essentially because if you were looking for orders with more than 3 products, that's not what you'd be getting in this instance!

Other aspects of note are that I had to specify the 'ship_mode' column in both where clauses as well as the quantity even though I wanted quantity to be more than 3 in both cases. If I had written, WHERE ship_mode = 'First Class' OR 'Second class', this would have returned an error because it doesn't understand where the second class is coming from. More still, if I had written WHERE ship_mode = 'First Class' OR ship_mode = 'Second Class' AND quantity > 3, then it would have returned second class orders with individual product quantities more than 3 and all first class orders. This is because it's taking the AND statement to connect the second class shipments and the OR statement has separated this from the first class shipments. During writing this blog though, I have figured out a secondary and quicker way to write this so that you don't have to write quantity twice, as you'll see in the second block of code. Using the brackets ensured that the ship mode statements were essentially grouped together so that the AND quantity statement was connected to both ship modes.

SELECT

order_id

,product_id

,ship_mode

,quantity

FROM orders

WHERE ship_mode = 'First Class' AND quantity > 3

OR ship_mode = 'Second Class' AND quantity > 3;

SELECT

order_id

,product_id

,ship_mode

,quantity

FROM orders

WHERE (ship_mode = 'First Class' OR ship_mode = 'Second Class')

AND quantity > 3;

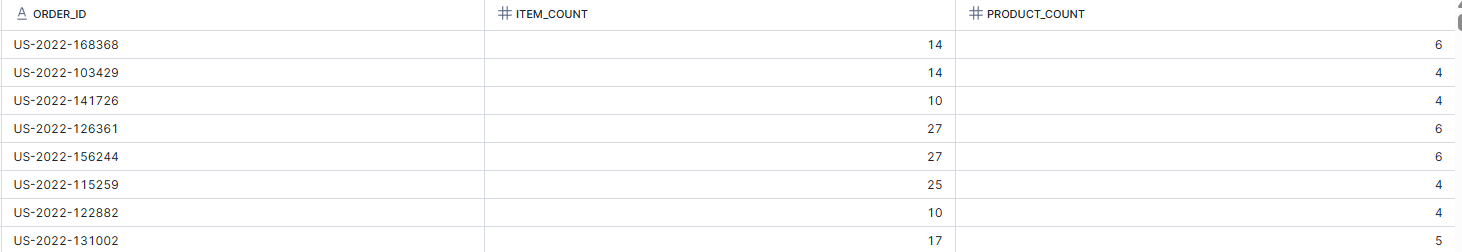

GROUP BY

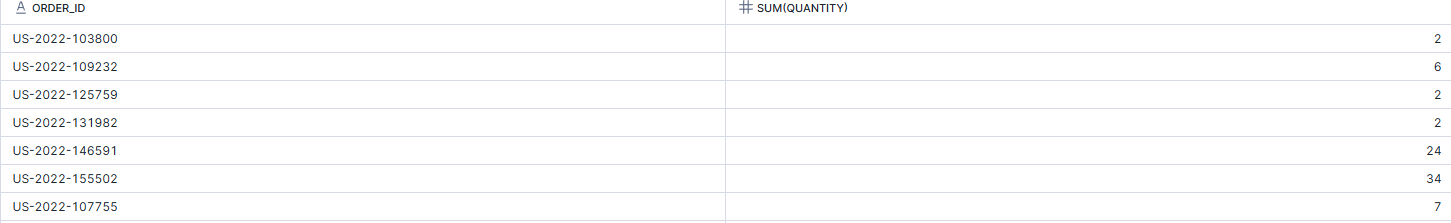

Group by acts as a facilitator to aggregation, specifying the level of detail that a calculation written elsewhere in the query should be performed at.

In the example below, I want to return all of the orders and the quantity of items in each order. To do this, I grouped by order ID as otherwise, each order would have been returned at the product level, as discussed before. As I had grouped the orders together, I had to aggregate my other columns as well since it wouldn't know which individual quantity value to return for the orders otherwise. The same issue occurs with string fields however it makes less sense to aggregate these if you're looking to return a string field, because this would then only show one value and not the whole picture. For example, if I used max(product_id) then I would only see one product ID still.

SELECT

order_id

,sum(quantity)

FROM orders

GROUP BY order_id;

HAVING

Having is another form of filter using a conditional format to eliminate false rows from the returned data. The distinction is that aggregations are used in the filter condition.

In the example below, I want to return the order and the quantity of items that were within the order, as well as the number of different products within it, where number of different products within the order is more than 3. I couldn't use WHERE in this instance because I have aggregated my product ID. I have also added a little something extra to this sequence of code by renaming my columns to ensure they make the most sense. I have done this with the 'as' and used underscores rather than spaces so it knows that I'm referring to a single column name.

SELECT

order_id

,sum(quantity) as Item_Count

,count(product_id) as Product_Count

FROM orders

GROUP BY order_id

HAVING count(product_id) > 3;

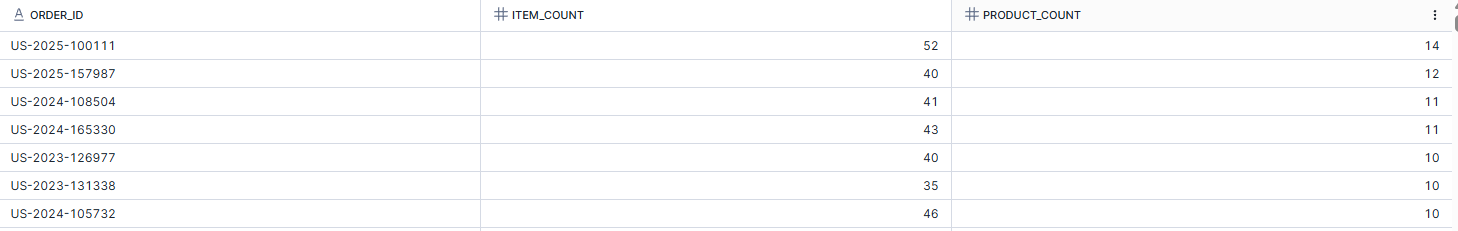

ORDER BY

Quite simply, order by specifies how the data is sorted when returned.

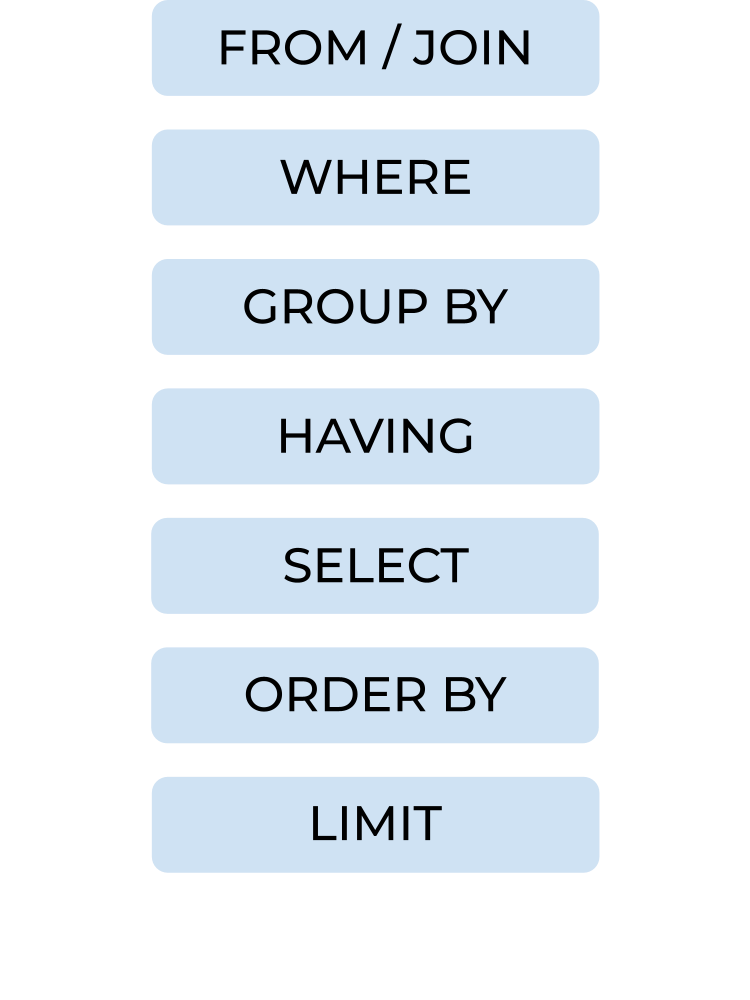

In the example below, I have used the exact same code as above but added that I want the returned data to be ordered by the count of product_id in a descending manner so that the order with the most products is at the top.

SELECT

order_id

,sum(quantity) as Item_Count

,count(product_id) as Product_Count

FROM orders

GROUP BY order_id

HAVING count(product_id) > 3

ORDER BY count(product_id) desc;

In the example below, I have repeated the same code but also added an extra order by clause with item count. In this instance, the data returned will be ordered by product count and then if orders have the same product count, they'll be ordered by count of items in the order. As I haven't specified the direction of the order by in the latter case, it has automatically assumed I want the data returned in ascending order. If this was a string value, it would be returned alphabetically by default.

SELECT

order_id

,sum(quantity) as Item_Count

,count(product_id) as Product_Count

FROM orders

GROUP BY order_id

HAVING count(product_id) > 3

ORDER BY count(product_id) desc, Item_Count;

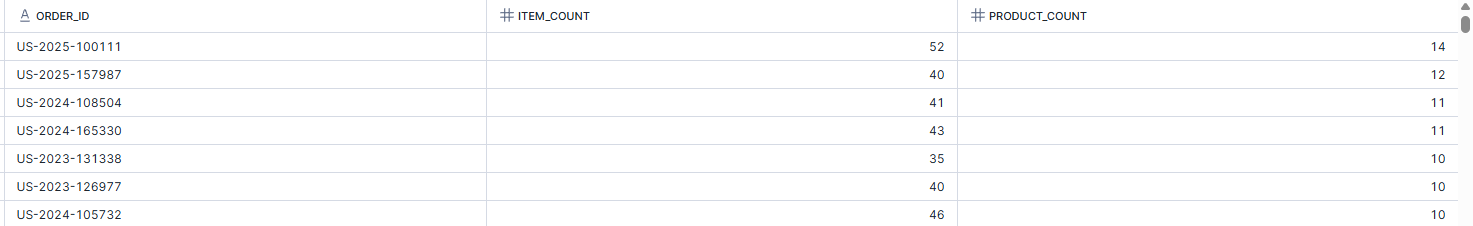

LIMIT

Limit specifies the first N rows to be returned by the query. It typically makes the most sense to use the limit clause with an order by as otherwise you're simply returning the first rows in the data without any rhyme or reason as to why these have been chosen.

In the example below, I have again replicated the same code as above but I want to return only the top 5 orders by product count and therefore have added the LIMIT clause. The slight downside here is that multiple orders have a product count of 10 and so it hasn't taken all of them, only the row within the 'top 5' and this row has been decided by the item count ordering.

SELECT

order_id

,sum(quantity) as Item_Count

,count(product_id) as Product_Count

FROM orders

GROUP BY order_id

HAVING count(product_id) > 3

ORDER BY count(product_id) desc, Item_Count

LIMIT 5;

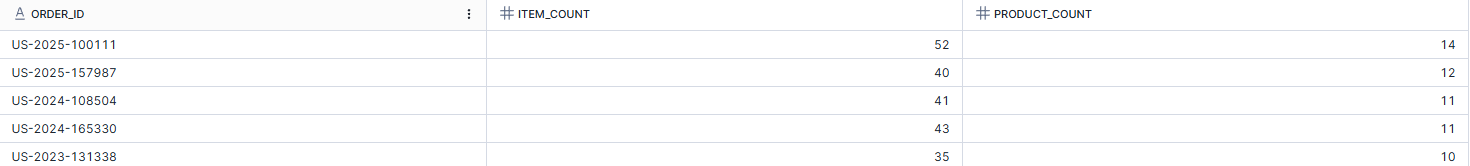

In the example below, I have used the same code but added an offset where it jumps to the second row as its starting point.

SELECT

order_id

,sum(quantity) as Item_Count

,count(product_id) as Product_Count

FROM orders

GROUP BY order_id

HAVING count(product_id) > 3

ORDER BY count(product_id) desc, Item_Count

LIMIT 5 OFFSET 1;

SQL Order of Execution

Following a rundown of the basic clauses, and the specificity of the order these must be written in, you might assume that this impacts the order that they're being processed in. However, somewhat confusingly the specific order that SQL likes for its query to be in is not the same order that it will execute the query in as you'll see below. I feel the ordering does make sense though when you carefully think it through.

For example, you start by looking at all of the data in your table(s). You then add any conditions that the rows must meet, grouping the rows accordingly and determining whether any related conditions apply. Now that the data is filtered, you can choose which columns you'd like to see in your returned data. You can specify how you'd like the data to be ordered and limit the number of rows that are returned.

There you have it - a quick breakdown of writing basic queries in SQL. Keep an eye out for some slightly more advanced SQL blogs as well as I'm looking to walk through sub-queries and CTEs in the next few weeks or so. Until next time, happy querying!